Spring Break 1969

Crazy Glen wanted to me to hitchhike to California with him. We were eighteen and it was spring 1969, so it seemed like the thing to do.

by Christopher Dow

Glen wasn’t really my friend, but he was my roommate, and we did hang out together some. We lived in Taub Hall, one of the old dorms at the University of Houston. I’m not sure why most people called Glen crazy. He wasn’t obviously nuts. There was no overtly irrational behavior, no wild-eyed rantings or brooding mutterings. He didn’t even do drugs, which was pretty rare for a young longhair in early 1969. That and the fact that he was a loner made some of my friends suspect him of being an undercover narcotics agent. I don’t think that was the case. I got to know him probably as well as anyone, and he seemed too screwed up and self-involved to be a government plant. Besides, illegal substances constantly flowed freely right under his nose, and no one was ever busted.

Glen did drink beer, and he insisted on doing it almost nightly in our dorm room, which often got him in trouble with the dorm authorities. Maybe that’s partly why we thought he was off, but looking back, our actions couldn’t have been any more rational since we were smoking pot and dropping acid in our rooms all the time. I don’t know what dorm life is like these days, but a lot of things we were involved in were probably more dangerous in spring 1969 than they are now, especially in Texas, where it wasn’t unheard of for a black political activist—namely Lee Otis Johnson—to be sentenced to twenty years in prison for possession of two joints handed to him by an undercover agent.

Glen had a habit of flouting authority that went way back. He was from Pennsylvania, where his father had the unusual dual role of prominent minister and member of the state legislature. With that kind of paternity, Glen had a lot to rebel against, and apparently, he spent a lot of wild nights sneaking out and getting drunk—the usual teenage preoccupation before more interesting drugs became popular. One night, so he said, he passed out in a cold rain and wound up with a case of pneumonia from which he almost died. He told me he never fully recovered and had a hole the size of a quarter in one of his lungs that was sealed with some kind of medical plastic.

I don’t know if it was true, but I did come back to the room one night to find Glen stretched out on the floor, unconscious. At first I thought he was feigning, because that wouldn’t have been out of character, but there was a slackness to his face and dead weight to his body that said he was really out and not just miming. I knew he wasn’t passed out drunk, either, because there was no odor of alcohol. I called the campus cops, but before they arrived, I managed to rouse Glen out of his stupor. He was still half groggy when he learned I’d called the cops, and he quickly staggered out the door and vanished into the night, leaving me with a seemingly crazy story to explain to the campus cops who showed up.

But there was something different about Glen that went beyond his flouting of authority. Maybe he did live near death and that gave his actions a certain edge that the rest of us didn’t have. Like I said, it didn’t manifest in overt craziness, but fairly frequently he’d do something pretty off the wall, like arguing with a street gang that stuck him up while he was on his way back from the convenience store with a six-pack. They had fun roughing him up, and then one of them slashed him down the breastbone with a switchblade. He came back, eyes glazed, with blood all over his shirt, and the rest of the year he proudly bared his chest to display the two-and-a-half-inch red weal.

Maybe I wasn’t much better off, though the scars were inside. I barely had any personality when I arrived at the University of Houston as a new freshman six months before, and I’d spent a good portion of that time zonked on pot and acid, habituating rock clubs, and generally destroying my academic prospects. But I was learning, or at least it seemed that way, even if the lessons had nothing to do with academics or degrees. So when Glen suggested we hitchhike to Los Angeles over spring break, I agreed. It would be an adventure.

Yes.

To prepare, we went out and each bought a small gym bag to carry our stuff. I’m talking about those half-moon-shaped, flat-bottomed vinyl bags with a zipper and loop handles on top. You don’t see them anymore—backpacks and gym duffels have replaced them, but those didn’t exist then except in Army surplus versions. At the time, the gym bags were ideal—cheap and easy to carry—and we were poor and traveling light. We also bought a black magic marker to letter signs. We figured we could find scrap cardboard along the way.

That was the meager extent of our preparation. When we left Houston, I had about forty dollars, a light jacket, a change of clothes, and my toiletries.

A friend drove us out I-10, just west of Houston’s city limits, and let us off. There we stood for a couple of hours with our thumbs stuck out and brandishing a cardboard sign with the words “San Antonio” scrawled on it in black magic marker. We weren’t ambitious enough to write “Los Angeles,” and anyway we figured that people who might give us a ride at least to San Antonio might not bother if we were advertising for a much longer journey. We’d settle for stages.

At last a car stopped, and we ran up. A young woman was behind the wheel. I reached the car first, hopped in the back seat, and shut the door, figuring Glen would sit in the front. Instead, he opened the other back door and slid onto the seat beside me. I couldn’t believe he did that, but like I said, he was prone to unpredictable behavior.

The young woman asked us where in San Antonio we were going, and we told her we were actually going to Los Angeles. She said she’d get us as far as San Antonio, we said that was fine, and that was that—all our conversation was used up during the first minute of a nearly four-hour ride. I felt sorry for her, driving all that way with two possibly dangerous, but actually numbskull, freaks in the back seat. For my part, I wasn’t a particularly good conversationalist, especially around women, so embarrassment kept my mouth shut. Maybe Glen felt the same, though he used to talk about having sex with his girlfriend back home. But maybe I’d just been taken in by his brash front, which undoubtedly masked deep insecurity.

After the young woman let us out in San Antonio, we stood for another few hours until late sunset, when a clean-cut guy in his mid thirties picked us up. He was driving a brand-new and very expensive Pontiac Grand Prix with dealer plates, and he was headed to Midland. That was off the I-10 path, but it was a hell of a long way across a hell of a wide state, so we got in. This time, anticipating Glen, I went ahead and sat in the front seat—a tactic I use the remainder of the trip.

The driver was a salesman for a car dealership in Midland, and the Grand Prix wasn’t his. It had been ordered by a rich oil man who lived in that West Texas pump-jack paradise. Our driver had gone to San Antonio to pick up the car and deliver it to the dealership. It was a fancy ride—plush and comfortable and fitted with all the amenities of its day. Since it wasn’t the driver’s car, he didn’t care if he stressed it. “Fuck him,” he said of the oil man. “If it breaks, he can buy another.” To prove his point, the driver drove at a pretty good pace. Not that the car was ever in danger of breaking, at least from speed. It was a powerful machine, and the highways of West Texas, including the state highways, are just made for eighty-five miles an hour, even at night.

Around midnight, we finally came to a town named Eden, which was little more than a bump in the road. Despite its name, it was no paradise—at least not for hippies. Our driver pulled into a gas station, and while the attendant pumped the gas, we all got out to stretch, take a leak, and get a soda. Almost immediately, an older man hurried out of the office and over to our driver.

“Get those boys back in the car!” he said, voice not especially loud but full of urgency. “Get them back in the car!” he repeated when we just stood there like idiots, wondering what he meant. Then we looked around and saw.

Across the highway was the local cowboy bar. Parked out front in the dusty, unpaved lot were a dozen pickup trucks around which lounged fifteen or twenty cowboys. Or rather, they had been lounging until they spotted us. Now they were clustering near the highway shoulder, looking us over as we stood spotlit in the glow of the gas station lights. And they were muttering among themselves. I couldn’t hear what they were saying, but they didn’t look very friendly.

These days, even cowboys and rednecks have long hair, but in 1969, long hair was tantamount to waving the Russian flag, shouting anti-American slogans, and assaulting upstanding womenfolk in the street. The movie, Easy Rider, which came out just a few months later, amply demonstrates how those good old boys of the South and West felt about folks who dared to be different. Conservative America did not recognize hippies and freaks as being fully human. Like Blacks or Hispanics, we were social anathemas and fair game for violence, as most of us knew from personal experience. The antagonisms depicted in Easy Rider were all too real and still are.

Actually, though, until that moment, Glen and I hadn’t thought too much about our long hair and hippie clothes. I guess we were just young, idealistic, and inexperienced in the ways of the real world. Most of our friends were like us, and no one at the university seemed to care, at least not enough to express their displeasure in gratuitous violence. Even the clean-cut Midland car salesman hadn’t mentioned our hair or attire. But then we’d never been to West Texas, and the rapidly brewing belligerence of those redneck cowboys across the road was plain to see. By now, some were gesticulating, and their voices grew in pitch.

We got back in the car.

The attendant finished pumping the gas, our driver paid, and we pulled back out on the highway. Six pickups, rear-window gun racks bristling with rifles and shotguns, pulled out of the kicker bar parking lot and began trailing us.

For the next mile or so, while we were still in town, we made a nice little parade—six “floats” depicting an extremist West Texas theme—including the fully laden gun racks—led by the grand marshal’s car carrying the grand marshal—that was our driver—and the two special guests of honor—those were Glen and me.

It was all rather nice and peaceful until we hit the city limits. Then the six floats roared into life—or was it death?—behind us, and the grand marshal stomped on the gas. In about ten seconds, we were all traveling at eighty-plus miles per hour down the two-lane blacktop. Ahead was only pitch-black desert night.

“What are we going to do if they catch us?” Glen asked after several tense minutes during which the only sounds were the roar of the Grand Prix's engine and the rush of wind. What a stupid question, I thought. They’re going to beat us until we die—or wish we had. That’s what was going to happen. Maybe we’d be lucky, and they’d shoot us right off the bat.

But the grand marshal just uttered an easy laugh. He knew something we didn’t. He was driving one of the most powerful and well-made American cars on the market, and not only was it brand new and built for speed and handling, it was full of gas and it wasn’t his. He was the grand marshal in command of this parade, and he knew it.

“I’m only playing with them,” he said. “Watch this.”

Seconds later, we were going a hundred and ten.

The cowboys chasing us valiantly tried to keep up. Their pickups were powerful work machines, and they could travel at a good clip, but they weren’t built for sustained high speed, and they certainly couldn’t take the curves like the Pontiac. Plus, the cowboys didn’t plan on driving hundreds of miles to Midland like our driver did. Gradually the pursuing headlights began to drift back in the darkness. At last, pair by pair, they were swallowed by the night until all were gone. It had been twenty minutes since we left town.

The grand marshal eased up on the gas, and the Pontiac slowed to eighty. He’d used American know-how and panache to whup American ignorance and bassackward thinking, and in the process, he’d saved a couple of innocent college kids from brutality and mayhem. He was a pretty damn good driver, too.

He turned to us, grinning.

“Nice car, huh?”

We grinned back. If I’d had the cash, I’d have bought a Grand Prix from him on the spot.

The rest of the ride passed in quiet darkness, the road hissing beneath the tires, the tiny towns and distant ranch house lights drifting by us like shadows of a dream.

“Look at that,” the grand marshal said at last, pointing.

Up ahead we could see a large area of sky glowing in the profound West Texas night, though we couldn’t see what caused the phenomenon. It was too early for Close Encounters of the Third Kind to have hit movie screens, or I might have suspected that the Mother Ship had arrived. But no, it wasn’t the Mother Ship, though it was probably just as alien.

“That’s Midland,” the grand marshal said, then he pointed off to another, fainter, more distant glow. “And that’s Odessa.”

The air was so clear and dark that the cities’ auras hovered in the dry atmosphere above them and could be seen thirty or more miles away, even though the towns themselves were still well below the horizon.

At about 4 am, on the near side of Midland, the grand marshal pulled over. It had been a good, long ride, and we were reluctant to leave the safe haven of the vehicle in which we had passed unscathed through certain travail. Who knew what rednecks waited for us on Midland’s nighttime highways? But it was the end of the ride. We got out and waved good-bye as the grand marshal exited into Midland’s radiance.

We may have entered the periphery of Midland’s glow, but there wasn’t much to see where we were except a dead-empty freeway interchange and the lights of a distant neighborhood. After about half an hour, a curious state trooper slowed, gave us the once-over, and drove on. Maybe he didn’t harass us since he knew that oil-patch roughnecks would take care of us as soon as the refinery shifts changed.

Another hour passed, and an old Chevy pickup slowed and stopped long enough to let us in. A middle-aged Hispanic man who spoke good English was driving, and maybe he saw us as potential fellow victims. We didn’t care what his reasons for stopping were, just that he made the effort. Luckily for us, he was going all the way to El Paso.

We were in the truck for only a short time when a terrible stench began to permeate the air. To me it was suffocating, but the driver seemed not to notice.

“What the heck is that smell?” I asked.

“Oh, that. That’s the oil refinery,” he replied, gesturing off to the side. Sure enough, there it was, replete with aerial plumbing, huge tanks, and even a few pump jacks.

I’ve lived near the Houston Ship Channel for many years, now, and have become familiar with such odors, but back then, I had no idea that oil and petrochemical products could be so smelly. Not that proximity and long association have made the odors any less pungent.

At last we left the odor behind, and by dawn, we were entering El Paso. The red morning sunlight on the rugged, barren hills and mountains was absolutely gorgeous, making it seem as if the earth itself was aglow and golden. Our driver got us back to I-10 and dropped us off at his exit. The air was dry and dusty though not yet hot. Where we stood, the interstate cut through the foot of a low hill, and right beside us was a steep cement embankment about fifty feet high. Over the top of the embankment sat a low-rent motel, its back to the highway.

We hadn’t been there more than fifteen minutes when we heard a voice calling.

“Hey!”

We looked around. A ride we’d missed?

“Hey!”

At the top of the embankment was a young blonde woman, about our age. We could tell she wasn’t a natural blonde because all she wore was a half-buttoned man’s shirt and a smile.

“We’ve got a room,” she called. “Come on up.”

I was callow enough to be intimidated by a mostly naked strange woman beckoning me to a strange motel atop a cement embankment in a strange city, but Glen got one look at the dark patch of hair showing beneath the shirt tails and started scrambling up the slope. I guess he had been having sex with his girlfriend. He didn’t even look back to see if I was following.

What else could I do?

I’m sure Glen thought he was going to get laid, but when we got to the room, we found it was occupied by another mostly naked young woman and a scruffy half-naked man in his mid twenties. All three affected hippie-type attire, but I could tell immediately they were vagabonds and maybe criminals, not flower children, freaks, or students.

We passed a few amenities back and forth, then the motel trio got down to business. They’d been in the motel for three days and didn’t have any money. So they said. Did we have any? If we did, they’d let us travel with them.

We’d be on a bus and not hitchhiking if we had any money, we told them. By now, Glen was beginning to realize he wasn’t going to get laid, though he might get screwed, and that we didn’t need to be here. After about half an hour, we extricated ourselves, left the motel room, and slid back down the embankment.

Our next ride, which came along about an hour later, was in a beat-up, light brown, ten-year-old Cadillac Eldorado driven by a man of indeterminate middle age looking about as shabby as his car. He wore a faded, light-colored plaid sports coat and equally faded slacks whose color might be defined as dingy, day-old Dijon mustard. He needed a shave and a toothbrush, but he gave a genuine-seeming smile when we got in the car. Next to him on the front seat was a tallish young woman in her early twenties who looked like she might be Indian mixed with Anglo. She wasn’t pretty, but she was attractive and built like a brick house, nipples showing beneath her tight, plain white T-shirt. She had long, straight, glossy-black hair and was missing one of her upper front teeth. That didn’t stop her from smiling, and her smile, too, seemed to be the real thing.

Glen and I had to crowd into the front seat with the driver and the young woman because the back of the Caddy was completely filled with clothes and other stuff and looked well lived in. This pair had been on the road a long time and probably were going to be on it a lot longer. They were friendly, though, and as we talked, it became apparent that they’d picked us up not from pity or to take advantage of us or out of the need for company but because it was the right thing to do for other people living on the road.

The ride was short, only to Las Cruces, New Mexico, but it got us out of Texas in time for our best ride yet. This was with a hippie couple in their late twenties. They were driving a ten-year-old Ford pickup and were going all the way to San Diego.

“Hop in the back,” the guy said, and we did. About fifty miles farther on, they stopped again for two more hitchhiking freaks, and then there were four of us in the pickup’s bed. The cowboys back in West Texas would have had a field day with that truck.

We spent all day in the bed of the pickup, traveling across America’s great southwestern deserts. Memory has compressed the transit to a few images and vignettes, but at the time, it was one great blur of sun-blasted sand and rock that seemed to go on and on forever. I’d never seen the West except in movies, and in one day I saw the whole thing in cross section with nothing between me and it but wind shear. We couldn’t talk because the wind blew away our words. All we could do was sit and watch the desert change from morning to afternoon to evening.

A highlight was passing through Tucson, which we did toward the late afternoon. The experience was surreal. One minute we were driving across harsh brown desert, and the next we were in the middle of green lawns and trees. Because the terrain was so flat, we couldn’t see the greenery except when the truck went up the overpasses over city streets. Every time we ascended, for a few seconds, we could see the suburbs, with their boxy houses, verdant lawns, and azure backyard pools, spread like a toy city across the otherwise barren landscape, then we’d come down to ground level and have it all disappear behind a facade of houses, buildings, and fences. Then, just as suddenly as it had all appeared, it was gone, and we were outside the city, where the desert remorselessly wiped away any hint that a green, leafy plant or blue swimming pool might reside within a thousand miles or a thousand lifetimes.

The sun went down, just about the time we approached the California border. The second pair of freaks had sleeping bags, and they crawled into them and went to sleep, but Glen and I, with our meager kits, could only sit in the cold desert night wind and shiver. And then the truck started to climb into the tail end of the Sierra Nevadas—between the Little San Bernardino and Orocopia Mountains—and the air turned bitterly cold.

Thank goodness the hippies in the cab took pity on us, stopped, and let Glen and me climb into the cab with them. The heater blew toasty air on our feet, and the couple’s friendliness warmed us in other ways. In two hours or so, we were in San Diego. The hippie couple dropped all four of us hitchers at a restaurant on Coastal Highway 101 then drove out of our lives.

The restaurant, part of a modest chain, was called Sambo’s, and it specialized, of course, in pancakes. I couldn’t believe that there was a restaurant called Sambo’s. This was a time when the Step-n-Fetchit and Mammy stereotypes were beginning to fall, black power and the natural look of the Afro were in, and even Aunt Jemima was on her way to a face lift. And here was Sambo’s, playing off a derogatory stereotype. Okay, yeah, Sambo was a smart young fellow who triumphed in the face of adversity and outrageous odds, but to name a breakfast restaurant after him? What a slap in the face to black people everywhere.

But it was late, we were hungry, and Sambo’s was just what we needed after a long ride across the desert. The four of us went in and ate. Once inside, I had to revise my idea that Sambo’s was a slap in the face to African Americans—it was a double slap because Sambo, as depicted in the menu and the illustrations on the walls, was white. I guess the owners of the chain figured that no black man could be as clever as Sambo, so Sambo must have been white. Or maybe, to give them the benefit of the doubt, they were trying to be politically correct twenty years ahead of the trend. Whatever the case, the plan, and the chain, utterly failed within a few years. Recently, I saw an old Sambo’s that had turned into an independent restaurant. Apparently, the new owners were on a shoestring budget when they started, because they kept the original sign and replaced only a single letter to read, Simbo’s.

After we ate, the other two freaks decided to remain for a time in San Diego. Glen and I got on the 101 going north and stuck out our thumbs. A couple of hippie chicks picked us up, though I can’t understand why two good looking young women would pick up such a scruffy, grimy pair as Glen and me. My long hair was a tangled, mopish mass after being whipped for fourteen hours in the back of the pickup during the ride across the desert, and my face felt pretty sunburned. Glen didn’t look much better than I felt, though he had a beard to help protect his face and his hair wasn’t as long. The girls took us up the coast for twenty miles or so and let us out. By now it was after midnight—the witching hour when the crazies came out. And one of them came along and picked us up.

He was a couple of years older than us, driving a Volkswagen Beetle, and seriously tripping on acid. He’d also probably taken speed, because he kept up an incessant stream of ranting and raving that was so voluminous and continuous it threatened to turn into a solid. Despite its density—or perhaps because of it—most of what he said was completely unintelligible.

At one point, he took his foot off the accelerator, drifted the car to the side of the road, and stopped. Suddenly and uncharacteristically silent, he stared through the side window as if mesmerized. Glen and I looked, too. Out there in the pitch blackness of the midnight Pacific Ocean, ragged lines and sheets of glowing electric blue were washing towards us. I’d never seen anything like it, and for a second, I thought that somehow I had contact high from the driver and was tripping, too.

“What is it?” I asked.

“Red tide,” the driver murmured. “Little creatures that glow when the surf stirs them up.” It was the most comprehensible thing he’d said.

We stared at the beautiful sight for about ten minutes, then the driver brought himself out of his trance.

“Wow, man,” he said as he accelerated back onto the highway. “I’m glowing, too.” And that was the last thing I understood, though he immediately resumed his aimless rapping and talked all the way to LA.

But at least he didn’t have a wreck, and he finally let us out, seemingly at random, on a madhouse morning rush-hour freeway. Houston’s freeway traffic has gotten that bad—or worse—in the thirty years since, but LA was an innovator and still remains tops in bad traffic. We didn’t get much attention from the drivers rushing by us, so after a couple of hours, we found a pay phone, and Glen called his aunt, who lived alone in a distant suburb west of the city. She came and picked us up and took us home.

As soon as we arrived at her house, I went into the bathroom and looked at myself in the mirror. My nose felt funny, and I wanted to see what was wrong. It was all white and puffy looking—not like the flesh was swollen but as if there was something wrong with the skin. Bending close to the mirror, I touched my nose, and the skin fell off into the sink.

I was too shocked to do anything but stare at the raw red thing that was my nose. It didn’t really hurt any more than a regular sunburn, but it sure looked weird. I wondered how I was going to explain to Glen and his aunt that my nose skin just fell off. I decided not to bother unless they asked. I flushed the skin and went back into the living room. They both looked at me a little strangely at first but quickly got used to my new appearance.

Glen’s aunt was a pleasant woman of about forty, recently divorced, and we stayed with her for a couple of days. She was happy to see Glen, though he seemed embarrassed to be there. We ate well and slept in beds, and she took us to Disneyland.

Nowadays, Disneyland isn’t any big deal. Today there are Disneyworlds all over the place, a lot of Six Flags, and many other large amusement parks of similar ilk, but back in the 1960s, Disneyland was what set kids’ imaginations afire. Sure, there was Coney Island if you lived in New York, or the Quassy Amusement Park if you lived in Connecticut, or Frontier City in Oklahoma City, or the amusement park at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. And there were a great number of other lesser amusement parks scattered across the nation. But if you were like most American youth who grew up in the American hinterlands in the ’50s and ’60s, you got your kicks only in the fall, when the state fair came alive. Or maybe you had to settle for the smaller county fair if you couldn’t make the state shindig.

Walt Disney had not only taken the concept of the fair’s midway, enlarged on it, and turned it into a year-round event, he’d constantly bombarded virtually every kid in the nation with images of his super amusement park. Disneyland was on TV, at the movies, and in magazines. For kids at the time, Disneyland was a bit like the Promised Land, only better, since you could actually go there, have a great time and maybe even be on TV, and then go home afterwards and brag about how great it was to your friends and classmates.

Naturally, I was excited. Glen’s aunt told us we’d arrived at just the right time. Until just a few weeks prior, Disneyland officials had barred hippies from enjoying the park. I guess they’d been worried that Disneyland might lose its homey image and family atmosphere with a bunch of stoned freaks running around, grooving on the rides and making fun of the straight people. But maybe the officials also had begun to worry about anti-discrimination laws, which those same hippies were doing their best to get enforced with regard to women and minorities. So the park finally had begun to allow hippies and freaks into its pleasures. It didn’t last. A few months later, I read a newspaper article stating that a massive influx of stoned hippies grooving on the rides and making fun of the straight people prompted Disneyland officials to once again close the park to longhairs. So it was indeed fortunate that I was there during that narrow window of opportunity.

I had a great time. Rode the rides, saw the sights, smelled the smells. It was smaller and dingier than I’d expected, but I was old enough to appreciate the mechanical wonder of it all. I was particularly impressed by the Abe Lincoln automaton because it kept shifting its weight from foot to foot as it stood there, delivering the famed Gettysburg Address.

That night, Glen told me he wanted to leave. Not LA, but his aunt’s house. Maybe it felt too much like home to him, with parents watching over his every move and stifling his restless, loner spirit. Or perhaps it was just too safe.

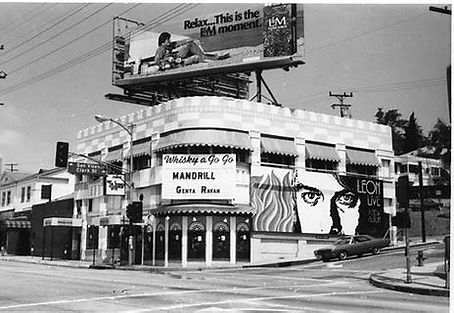

Besides, we hadn’t hitchhiked halfway across a continent just to spend our precious few days cooped up in a suburban house. So after breakfast the next morning, we bid his aunt adieu, hopped a city bus, and headed into downtown LA. We wandered around for a while and finally found our way to Sunset Strip. I knew the street from the television show of the same name, and supposedly there were good rock clubs along it where some of the great rock acts of the day—such as Love and The Doors—had gotten their starts. I’m not sure what I expected of this fabled drag, but I remember feeling faintly disappointed that it wasn’t constantly hopping. It looked like any other sallow, seedy neon drag. We failed to locate the Whiskey a Go Go, and we couldn’t find a single club that we wanted to visit.

We stayed in the Diggers’ crash pad, which was a real experience. The Diggers were a hippie sect based on simplicity and communal living, and their crash pad, located in a decrepit one-story building a few blocks off Sunset Strip, was a haven where homeless hippies could find a safe place to sleep. It was pretty much a homeless shelter that catered to hippies. Maybe I should say "stay" instead of "sleep," since I didn’t get much of that in the two nights we were there. One guy snored constantly and loudly, and another, just a couple of sleeping spaces away from me, was suffering from heroin withdrawal. He was sick and moaning and groaning all night long and getting up every ten minutes to vomit in the toilet. But we were off the streets, and that was probably good. Not that we were in particular danger from other hippies. LA was a little like West Texas—it was the establishment that was dangerous.

My first inkling of that fact came soon after we arrived at the Diggers’ crash pad. It was early evening, and we decided to go out and take a stroll on the Strip to see what was happening. We stashed our stuff with the Digger clerk and headed out the door. We turned onto a narrow side street that would take us the few blocks to the Strip, and a couple of blocks later, we came to an intersection where a second street met the street we were on. On our side of the street, the intersecting street devolved into a service alley that ran between the buildings. This intersection was protected by a traffic light, which showed red for traffic on our street and green for the intersecting street and alley.

It was 8 pm, and though there was some traffic up on Sunset, a couple of blocks ahead of us, no cars were bothering with our street or the intersecting one—and certainly not the alley. So, without a pause and without a second thought, Glen and I walked on across the alley.

Not a single car had been in sight as we began to cross the alley, but by the time we’d reached the far side, twenty feet distant, three cars were plainly evident—mostly because they were screeching to a halt in a ring around us, roof-top lights blazing, headlights pinning us to the wall in their stark glare.

The cops.

LA cops.

There were two in each car, and to add to the excitement, a seventh on foot patrol was drawn like a moth to the lights.

Seems Glen and I had committed the heinous crime of jay-walking across the alley. We were searched and interrogated for nearly half an hour. Maybe I should say we were harassed for half an hour. I guess things were slow out on the Strip, and the cops needed something to do to work off their testosterone-fueled aggression. At last, we were each given a ticket for jaywalking—the fine was $10—and told to watch our asses. Since I lived in Texas, not California, I failed to pay the fine. But I did keep the ticket for several years as a souvenir.

In retrospect, considering the reputation the LAPD had built over the years with hippies and any sort of minority, we were extremely wise not to crack wise with them or they’d probably have cracked our skulls. And the political climate certainly was ripe for that at the time, as illustrated by a second incident that highlighted the dangers of LA culture.

It happened the next day, after Glen and I again hopped a city bus, this one headed for Santa Monica. We wanted to see the beach—the Pacific, man!—even if the water was too cold for swimming. So far, the only glimpse of the Pacific we’d had was driving up the coast highway with the tripped-out freak a few nights before, when we’d seen phosphorescent blue waves rolling in from dark infinity.

We were on the bus a long time—maybe an hour—and during the ride, the passengers were predominantly poor working folks and old women. The old women all wore cotton print dresses and sported “Re-elect Mayor Yorty” pins. Sam Yorty was LA’s notoriously arch-conservative mayor. It wasn’t an election year—the elections had happened the previous November, about five months earlier. I couldn’t help but wonder why election pins were in evidence so late. Maybe the women kept wearing the pins in a show of post-election solidarity, sort of like a club corsage. Or maybe they’d just forgotten they had them on.

When Glen and I got on the bus, there were only three empty seats, all of them on those benches that face inward at the front of the bus. Glen sat right behind the driver, and I sat next to him, with the sole remaining empty seat to my right. At the next stop, two of Mayor Yorty’s gerontological pep squad stumped up the steps and onto the bus. I got up and offered them my seat. They took it and the remaining vacant one, their lack of a thank you accompanied by suspicious glares.

I hung onto the overhead bar for a few more blocks, then the front seat immediately next to the stairwell came open, and I sat down. The bus jolted on for a few more blocks, when out of the corner of my left eye, I saw another Mayor Yorty acolyte shuffling up the bus aisle. This woman had to have been eighty or more, and she had absolutely no business being on her feet on a moving bus. The bus was closing in on the bus stop as she came between me and the driver, and suddenly the car in front of the bus stopped. Our driver hit his brakes, and the old lady toppled forward, taking a nosedive down the stairwell.

Instinctively, I grabbed her arm and managed to keep her from going down any but the first step. She didn’t even hit her knees, though the effort nearly wrenched my shoulder out of its socket. I was a scrawny hundred and twenty-five pounds, and using only one arm to grapple and haul a nosediving hundred -and-sixty-pound old woman wasn’t part of my physical repertoire.

I got out of my seat to help her back on her feet, when a strident, cracking voice cut the air. It came from the old woman to whom I’d given my seat moments earlier. She was sitting ramrod straight, pointing at me like a prophet of doom, eyes aflame with righteous indignation.

“He tripped her!” she shrieked. “I saw it! He tripped her!”

Feeling helplessly railroaded into a guilty verdict though I was innocent of the charges and had in fact acted the hero and nearly dislocated my arm in the process, I looked up at the bus driver, who was right there and had seen everything. He looked back at me. He didn’t say anything, but his lips drew into a thin line, and he rolled his eyes. I understood instantly that he had to deal with the Yorty pep squad daily—hourly—and that this incident rated only a footnote in his book.

I finished assisting the old woman off the bus and got back in my seat, all beneath the baleful glare of the woman who accepted my former seat then falsely accused me. She continued to poke hot visual holes in me until she and her friend debarked a few blocks later. As they stood and moved toward the door, I was sorely tempted to pretend that I was going to trip them, but I prudently refrained.

Santa Monica was a beach with lots of sand, cold water, and a slightly nippy wind. Even so, a fair number of people were out, enjoying the beautiful weather. We stayed for a couple hours, warming in the sun, then bussed back to the Diggers’ crash pad. By then, thankfully, Mayor Yorty’s pep squad were all safely ensconced within their homes, and the ride was uneventful.

After one more night in the Digger’s crash pad, we left LA, beginning with a bus ride to the edge of the city. Our first real ride was with a guy about thirty. He wasn’t going out I-10, but he was headed vaguely east—to Las Vegas—so we got in. He played a lot of ’50s rock-n-roll on an 8-track tape player—his only concession to more up-to-date music was Velvet Underground’s first album. When he learned that I liked the band, he played the song “Heroin” for us several times. It's a great song, but I couldn’t appreciate it too much since I hadn’t had enough sleep the last couple of nights because of the guy on heroin withdrawal at the Diggers’ pad.

Our driver actually drove us completely through Las Vegas, explaining that he was going to take us east of the city before he let us out. It seemed that Las Vegas cops didn’t like hippie hitchhikers any more than the LA cops or West Texas cowboys did. He took us right past all the big hotels and casinos, so I got a good look at Las Vegas. I know several people who love Vegas and go there whenever they can. I think I’d get bored—I don’t gamble, drink, or whore, and those strike me as Las Vegas’s primary attractions. Oh, yeah, I guess now there are magic shows, Cirque du Soleil, overblown cabaret acts, and other fare, but I rode through before Vegas became “family oriented.” Back then, it was “crime family oriented.” This was about the time in which the middle scenes of Martin Scorsese’s Casino are set.

We drove east of Las Vegas and over Hoover Dam before he let us out. You can’t do that anymore. Not since 9/11. He returned to town, leaving us faced with having to work our way back to I-10 down the scant ribbon of US 93. Three local boys in a late-model Chevy Bel Air gave us a start.

They were whoopin’ and hollerin’ and wavin’ and drinkin’ beer. They’d been drinking beer for some time, by all appearances. That was fine by Glen, who joined in with them, but I didn’t drink and was worried about the way the driver couldn’t seem to keep in his own lane. Not that it mattered, since traffic was virtually nonexistent on this two-lane desert blacktop, and in the desert valleys, you could see anything coming for at least five miles. But just because the driver could see something coming from five miles away didn’t mean he wouldn’t hit it when he got to it, and he was driving at an erratic seventy-five miles per hour—fast enough to cream us all even if he chose a telephone pole to pile into instead of an on-coming vehicle.

Then a Pontiac Grand Ville convertible roared passed us, and if I thought the drunken whooping and hollering had been loud before, it reached pure crescendo when our local boys spotted the two women in the front seat. They were young, blonde, and beautiful in the way of Vegas showgirls, and they were coming from that direction. And they were topless, catching some desert rays to encourage that all-tan look. The driver clutched a T-shirt across her breasts long enough to pass us, but the passenger simply bent forward until we were behind them.

Our drunken driver developed a foot that was heavy in direct inverse proportion to the lightness of his head, and in seconds, we were careening after the topless women at eighty-five. Then ninety, then a hundred. Unfortunately for our drunken chums, a Grand Ville had far greater power than the overloaded Bell Air, and though our driver kept his foot to the floor, the girls were soon the requisite five miles ahead and lost to sight. Our driver had been too drunk to hit what he’d aimed at.

It made a nice bookend to the chase through West Texas, though. Each had involved inferior vehicles chasing Pontiacs, but in West Texas, we’d been the pursued, and now we were among the pursuers. And both chases had proved fruitless, thwarted by the pure V-8 horsepower beneath the hoods of big, expensive American cars.

The drunk kids let us out soon after, and we caught a ride with a thankfully sane and sober businessman heading into Phoenix. Our driver let us out on the eastern outskirts of the city at about 10 pm. At least we were back on I-10, and it was a straight shot back to Houston.

Or so we thought.

We stood on an entrance ramp until 1 am, when a somewhat dilapidated dark blue Ford sedan stopped about fifty feet beyond us. The back door opened invitingly, and Glen and I ran up and jumped in. The car took off and was on the highway before we could look at each other and think that maybe we'd made a mistake in getting into this car. We didn’t know it, but our straight shot back to Houston was about to take an instructive and unsettling detour.

Our driver, still accelerating onto the highway, turned and growled, “Are you flower children?”

It sounded like a threat, and the driver looked threatening. He was a rough-looking man in his late forties or early fifties, wearing a grimy plaid shirt and a beat-up black leather jacket. Coarsely cut dark hair stuck out from beneath the beret on his head, and gold loop earrings festooned his earlobes. He had tattoos on his cheeks, which hadn’t seen a razor in several days.

The guy riding shotgun couldn’t have been a greater contrast, though no less strange. He was nearly gaunt and wearing fancy and immaculate dude cowboy clothes. Black dude cowboy clothes. All black. His hat was black, his shirt was black, his pants were black, his boots were black, his string tie was black, his hair was black, and his upper lip sported a thin little black mustache. Perched on his long, sharp nose was a pair of black wrap-around sunglasses. I wondered if his underwear was black, too.

Remember, it’s the middle of the night in the middle of the desert. If there hadn’t been the illumination from the dashboard lights and passing cars, this guy would have been invisible. I wondered just how much he could see through his blackened lenses. Unlike his companion, his cheeks were neat and crisp.

“Uh, no,” Glen stammered. “We’re students.”

“Ah,” the man with the tattooed cheeks nodded sagely. “Scholars. What school you go to?”

Glen told him, and the guy introduced himself and his friend. He was Gypsy and the black-garbed cowboy was the Kid.

The Kid nodded a greeting.

“And this is Maisy,” Gypsy said, gesturing to the seat between him and the Kid.

We peered over, and lying there was a smallish, three-legged female mutt nursing a fresh litter of pups.

Gypsy and the Kid were truck drivers. They’d just dropped off a truck in Phoenix and were on their way home. These pleasantries over, Gypsy abruptly swerved onto the next exit ramp.

“We’ll get out here,” Glen and I said in unison as the car left I-10, but Gypsy didn’t bother slowing to barely sane ramp speed. In five seconds, we were on a two-lane blacktop, the lights of Phoenix fading into the darkness behind us as we headed north, into the desert.

“Naw,” Gypsy said. “Trust us. We’re truckers and this is a trucker route. You’ll get lots of rides up this way.”

Yeah, right. In the hitchhiking I’d done up to then and all I did after, I’ve only been picked up once by an eighteen-wheeler. But there wasn’t much we could do except jump out, and by now the car was going sixty-five. We’d just have to sit out the ride with Gypsy, the Kid, and three-legged Maisy.

Gypsy liked to talk, and he kept up a steady stream of it, mostly about trucking life, until about the time we drove through Superior. That was when he began telling us about his and the Kid’s involvement in the local KKK. He told us, among other things, how they and a bunch of their buddies “took this nigger out into the desert and strung him up.” What fun it was.

There was no way to know if he was telling the truth or just trying to freak us out. He certainly did the latter. But just as easily as he’d started the KKK diatribe, he segued into something else, though I couldn’t pay much attention. All I could think of was their purported victim’s fear and anguish because I was feeling the fear myself and expecting the anguish. After all, people who would commit heinous crimes against others because of racial differences wouldn’t hesitate to do similar things to “commie hippie scum”—especially if we were “scholars,” which also meant “intellectual commie bastard scum,” to a redneck America that then was preaching “Love it, or leave it.”

A few miles before we reached Globe, Gypsy abruptly and without a word twisted the wheel, and the car spun off the road and lurched into the pitch-black desert. In an instant, fear filled me completely. I looked at Glen, who was staring back at me with bottomless pits of eyes that said he was feeling like I was—that we were about to experience the final moments of our lives in the middle of the desert at the hands of two insane truck drivers who would later joke with their buddies about the two commie hippies they strung up. What fun it was.

The car jolted on for another couple of minutes, and I was beginning to grope for the door handle, thinking about jumping out and trying to escape into the darkness, when suddenly Gypsy hit the brakes and the car ground to a stop in a clatter of gravel. This is it, I thought as dust billowed around the car and across the headlight beams. Where’s the rope?

Then the dust began to drift and settle, revealing a trailer home, half-obscured by weeds and cactus, sitting just in front of the car. The Kid gave Maisy a pet, nodded good-bye to us, got out, and sauntered to the trailer.

The fear that had ballooned inside me collapsed, leaving a stunned void. We were just dropping off the Kid at home.

Into the void rushed a blessed breeze of relief that buoyed my spirit. It wasn’t my time to die quite yet. And fluttering on that breeze was an amusing note: During the hour and a half we’d been in the car, the Kid hadn’t said one single word.

Gypsy stayed just long enough to light the Kid’s way to the door, then he turned around and, in a few moments, steered the car back onto the highway.

“Now, where was I?” he said. “Oh, yeah. This truck stop up here. I’m going to drop you off there. I know the waitress, and I’ll tell her to take care of you. You’ll do fine. A truck’ll pick you up in no time.”

Yeah, right.

A little way past Globe, Gypsy pulled into the scant parking lot of a ramshackle truck stop that was open despite the fact that it was around two in the morning, the parking lot was empty, and we hadn’t seen a single truck since leaving I-10. It wasn’t really a truck stop but a diner in dire need of paint with a couple of diesel and gas pumps out front. Gypsy took us inside and introduced us to the waitress, who gave us a desultory nod. As soon as we went back outside, she forgot all about us. Then Gypsy parted company with us, vanishing like an enigma into the desert night.

We stood out on the pavement about a hundred feet beyond the diner for more than an hour, and not a single truck came down the road from either direction. Nor were there any cars. I wondered what kept the diner open all night. Then a truck pulled up. The driver got out and went inside. He came out half an hour later and ignored us as he pulled out of the parking lot and drove off.

A little while later, another truck came and went. And another. Okay, there were trucks, but they sure weren’t picking us up.

At last, a car pulled into the parking lot and a big Jewish kid about our age got out. We knew he was Jewish because of the black yarmulke he wore. He barely had the door shut before we were next to him.

“Hey,” Glen said. “Would you give us a ride out of here?”

The kid, who looked pretty straight, wasn’t too excited about having a couple of raggedy freaks hit him up for a ride in the middle of nowhere in the middle of the night.

“I’m only going about twenty miles up this road before I turn off,” he said, hoping to dissuade us, but hell, that was twenty miles farther on.

“That’s good,” I said. “We’ve been stuck here for hours. We’re just trying to get back to school.” I added this last to let him know we weren’t a threat to him, since he was probably a student himself going home for spring break.

“Okay,” he said. “Get in. I have to use the rest room. I’ll be out in a few minutes. Be careful of the strawberry plants. They’re for my mom.”

We got in the car, and sure enough, half the floor in the back was covered with little plastic planters sprouting tiny seedlings. The driver came out a couple of minutes later, and we left the truck stop behind. About twenty miles farther on, he stopped at a nondescript side road.

“This is where I turn,” he said, obviously glad to get rid of us.

We got out, and he turned onto the side road and was gone. I didn’t know it then, but there’s nothing up that way for more than a hundred miles but Indian reservation—kind of a strange place for a Jewish kid to grow up.

Dawn was beginning to light the sky, and a scattered handful of cars and pickup trucks were drifting up and down the road, but none of the ones going our direction stopped. Then, just after the sun peeped over the desert landscape, a pickup truck, its bed filled with roped-down mattresses, pulled up beside us.

“Hop in, boys,” said the fiftyish, friendly faced man behind the wheel, and we did.

“Where you boys headed?”

“Back to Houston,” I said.

“Well, I’m just going to Safford, but I’ll take you that far.”

Our driver turned out to be a really nice and generous fellow. He got the basic outline of our journey, and said he admired us for being so adventurous. He didn’t live in Safford—Arizona, that is—but he owned a motel there, and he was taking the load of mattresses to the motel. The motel was on the leading edge of town, and about an hour later, he pulled into the parking lot. We got out, thanked him, and turned to walk up to the highway, when he stopped us.

“You boys must be hungry. Come on in. I’ll stake you to a meal.”

He took us inside, told the waitress to give us anything we wanted on the house, then left to unload the mattresses.

We ate. And ate some more. We hadn’t had a real meal since dinner at Glen’s aunt’s house four days earlier. Toward the end of the meal, the motel owner came in, sat down with us, and had some coffee.

“If you boys are still in town tonight, come on back here, and I’ll give you a room for the night free of charge.”

We thanked him but said we’d probably be back in Texas, at least, by nightfall.

Maybe he knew something we didn’t.

At about 8 o’clock, we left the motel, walked about a hundred yards down the highway, and stuck out our thumbs.

By eleven, every yahoo in town had driven by us at least twice, gawking, and many three or four times. Some of them shouted insults and obscenities, some threw beer cans at us, and a few swerved dangerously close. The winners were three teenage girls in a pickup. They came by us four times, and each time, they’d slow down like they were going to pick us up, then they’d peel out, laughing wildly at their clever joke and waving gaily out of the windows. Their fourth time around, they threw a Coke can at us. I guess they were too young to drink beer.

By 1 pm, we were thoroughly tired of being the main attraction in town, and we certainly weren’t having any luck catching a ride. Figuring it was because we were on the highway heading into town, we decided to go to the outbound side of town where we might have better luck—anybody going our way would be leaving this unfriendly place.

It took us thirty or forty minutes to walk from one side of Safford to the other. Along the way, we could see the stark, grim walls of a federal prison looming over the landscape. It was one of the biggest employers in town. I later learned that David Harris was incarcerated there not long after Glen and I passed through. Harris, who was then married to the folk singer Joan Baez, was the counterculture’s most famous antiwar protester, having gone to prison rather than fight unjustly in Vietnam. I wish I’d known at the time that he’d soon be in that prison. It would have set just the right mood to appreciate Safford. As if the girls in the pickup and the rest of the yahoos hadn’t done that already.

The other side of Safford was a lot quieter. Here, the highway was narrower and wound out of the city instead of arrowing straight in. And there were some trees. We stopped just up the road from a little burger shack that was set up near a small train yard where half a dozen boxcars sat on a siding. We were there for several hours, and although no one gave us a ride, no one came by to harass or throw beer cans at us, either.

At about five, a VW Beetle stopped. Inside were three hippieish kids about our age—a boy, who was driving, and two girls.

“You trying to get out of town?” the guy asked. There was something about the way he said it that relayed hidden information. Maybe it wasn’t a question.

“Yeah,” we replied in a tone that indicated understanding.

“We live here, so we can’t take you far,” the boy said. “But there’s a rest stop about twenty miles out. Maybe you’ll have better luck out there.”

“Anything’s better than this,” we said, squeezing into the back.

The driver, like us, was a college freshman, and he’d come home for spring break. He was friends with the two girls, who were sisters, one a high school senior and the other a junior. The girls’ parents had come to Safford a couple of years earlier to teach Spanish in the high school, but their jobs had been terminated because they were too liberal. The family was moving at the end of the school year. They all hated Safford, and Glen and I readily sympathized.

They dropped us off at the rest stop, wished us good luck, and headed back to town.

We’d thought that anything would be better than Safford, but now that we were here, we weren’t so sure. The rest stop consisted of a wide place on the shoulder and a rusted, gut-shot, fifty-five-gallon drum containing about sixty-five gallons of rotting garbage. More was strewn on the ground beneath it. All around us stretched flat desert, with distant mountains humping the horizons on either side of the road. If it had been midday, it would have been a frying pan. Now, with the sun going down and a cold wind sweeping across the plain, it was turning into an icebox.

In the couple of hours we stood there, the cars and pickups that passed were all obviously locals. Maybe they were checking up on us. It didn’t look like anybody going any distance was leaving Safford tonight.

Glen and I discussed our options. We could stand here and freeze our asses off waiting all night for a ride, or we could, somehow, get back to Safford to the burger stand. We could eat a burger and then spend the night in a boxcar. We even toyed with the idea of trying to hop a freight going east. The latter was Glen’s idea, but the colder it got, the more I took him seriously. By seven, we’d moved to the other side of the highway, heading back into Safford.

Astrophysicists have, during the last few decades, discovered that black holes—places that suck up everything, including light, space, and time—are scattered throughout the universe. It’s absolutely true, and there is such a place right here on Earth called Safford, Arizona. We’d struggled like hell to get out of this singular burg with its maximum security prison holding those who couldn’t escape the system, and literally hundreds of cars and trucks had passed us as we tried to free ourselves from its warping gravitation. Yet we were there on the other side of the road for less than five minutes when the first vehicle that came by stopped. Safford was easy to fall into, but getting out of it would require a major alteration of the laws of physics.

We ran up to the vehicle and got on.

I say on, not in. It was a dune buggy with only two bucket seats, and those were occupied by the man driving and his woman passenger. They were coming back to town after a day of fun in the sun, tearing up desert dunes. Glen and I perched on the back of the frame, whipped by the freezing wind, clinging to the cold metal with one hand and our gym bags with the other, trying to keep our flapping clothes from getting caught in the engine's whirling pulley or fan blades, and watching the road whiz about two feet beneath us at sixty or seventy miles per hour.

The dune buggy people let us off at the burger shack, which, to our consternation, was now closed. So much for dinner. And the boxcars were all locked up. Without enthusiasm, we resumed our position beside the road at the very spot where the young freaks in the VW had picked us up three hours earlier.

About twenty minutes later, the same VW with the same three occupants pulled up beside us.

“What happened?” the driver asked.

We told them we’d been cold, hungry, and thirsty and had come back to eat, but the burger shack was closed.

“Get in,” said the older girl. “We’ll take you home with us.”

“Won’t your parents get mad?” I asked.

“Naw. We told them about you, and they were concerned. They sent us out to check on you. That’s why we’re here. It’ll be all right.”

And it was. Their parents hated Safford, too. They welcomed us, fixed us dinner, dragged out sleeping bags so we could spend the night, and generally made us feel right at home. After we ate, the boy, the two girls, Glen, and I squeezed back into the VW and drove out into the country. The boy stopped near an irrigated field of short, green grass that must have covered a couple of thousand acres. I guess it was part of a turf farm.

We walked out into the middle, lay on the downy turf, and watched the incredibly spangled sky. Everyone knows how clear and beautiful the desert night sky is. Everyone, that is, except the population of Safford. Too bad they never look up to consider the wonder of existence instead of harassing innocent people who were different and running their federal penitentiary where they locked up those same different people. The only time they stopped to wonder was when they wondered what those damned stinking hippies were doing in their town.

But the night sky was gorgeously mysterious and our newfound friends companionable, and the grim realities of Safford seemed light years away.

The next morning, the girls’ mom fixed us a hearty breakfast, shoved big sack lunches into our hands, and sent us off with her daughters and the boy, back out to the rest stop.

“We’ll check on you,” she promised. “If you’re still there tonight, we’ll bring you back here.”

Our friends let us off and chugged back to town. I don’t remember the names of the boy or the younger girl, but the older girl’s name was Molly. She and I wrote to each other a few times during the next year or so, but we eventually lost touch.

Glen and I were set for another long wait at the rest stop, but only half an hour went by before a car stopped to give us a ride. I hopped into the front seat, Glen into the back, and Safford soon disappeared into the past. Our friends may not have altered the laws of physics, but at least they’d broken Safford’s black-hole gravitation and helped set us free.

The guy driving was about thirty-five. He said he worked at a small airport, and he gestured vaguely to the desert north of the highway. We hadn’t been in the car ten minutes before his right hand crabbed across the seat and started trying to grope my thigh. I wasn’t interested and shove it off. It came back, and I shoved it off and put my gym bag in my lap. He stopped the car.

“This is where I turn,” he said, though there wasn’t an intersection in sight.

I didn’t care, and we got out, though Glen was puzzled by it all until I told him what had happened. Luckily, we didn’t have to wait long for our next ride, and it was a good one—a young married couple going all the way to El Paso. They were nice enough to take us completely through the city before dropping us off on I-10.

Back on I-10, back in Texas, with a straight shot home.

Yep, we’d had similar thoughts before.

A couple of hours later, just after dusk, a big, new American station wagon with two guys inside stopped to give us a ride. The man behind the wheel couldn’t have been more incongruous for the archetypal family machine he drove. He was a big guy—large and beefy without being fat—and about thirty. His coarse black hair was edging over his ears, and it was raggedy, as if it was growing out from a crew cut. His coarse beard hadn’t seen a razor in several days. He wore old Marine fatigues. The shirt’s sleeves and insignia were cut off, and it was unbuttoned. Around his neck on a thick gold chain hung a heavy and incredibly ostentatious ersatz gold peace symbol about five inches in diameter. It lay on his hairy chest like some kind of talisman. Military and arcane tattoos colored his arms, and scuffed black military boots completed a spectacle that was altogether imposing and intimidating.

But he smiled when we got in, and said loudly, “How’s it going? How far you wanna ride? I’m goin’ all the way.”

The passenger was another freak hitchhiker like Glen and me. The driver had picked him up just west of El Paso, and he was headed for somewhere on the East Coast.

The driver had been in the U.S. Marines until a few weeks earlier, when he’d mustered out. He said he’d done three tours in Vietnam, and though there was nothing to prove this true, we didn’t doubt him. He was wild and a bit crazy, like a beast kept caged too long and bursting with energy to be free. Or a beast totally unused to cages who now saw one at the end of the trail.

The car wasn’t his—it belonged to some upper-middle-class family that had moved from LA to Atlanta, and he’d contracted to drive it to Atlanta for them. He’d left LA only that morning, which meant he was really pushing it to have made El Paso by dusk. And the car wasn’t the only thing that was speeding. He had a bottle of amphetamines to keep him alert, energetic, and driven.

And talkative. He drove and rapped about how cruddy the military was and how terrible and craven officers were, and how being in Vietnam had been good and bad and scary and satisfying, all at the same time. He talked about the weirdness of being immersed in such a totally different culture and how the Vietnamese people were as sophisticated as they were barbaric, as sly as they were courageous. And he told us, but didn’t dwell on, some of the terrible things he’d seen and done. He spoke with great rapidity, in great detail, and with total conviction, and the three of us sat and listened and tried to remain as calm as possible.

Remaining calm in a car pushing a hundred and twenty at night isn’t easy, particularly when the driver has been through hell and has accumulated a certain contempt for human life, especially his own, and is steadily popping speed. The fact that large sections of I-10 were under construction and he had to veer off onto treacherous dirt-road detours didn’t phase him a bit. Or slow him down. At one of these detours, the pavement dipped abruptly to the dirt road, and for a moment, the heavy station wagon was airborne before it crunched onto the detour, lurching and swaying dangerously.

“Guess I’d better take it easy,” the driver commented with a mordant chuckle. He let off the gas, but we were going so fast that the station wagon decelerated for several seconds before the speedometer needle separated itself from the peg at one-twenty and descended to one-ten. He deemed that speed sufficiently reduced to make it safely through the rest of the detour.

Not too far west of San Antonio, the driver caught sight of a sign that pointed the way to a nearby town, and he whipped the station wagon, squealing, onto the exit ramp. The town was Johnson City. He said he just had to see the town of the great president who’d made him go to war.

Personally, I wasn’t anxious to leave I-10. Too many potentially ugly things had happened during the last ten days, and most of them had occurred off the interstate. Nor was I interested in meeting face-to-face the sort of redneck cowboys who had chased us across northwest Texas. But I didn’t suggest to Glen that we ask the driver to let us out. I suppose by this time I was ready to accept whatever fate had in store. Maybe we’d met a certain degree of mortal danger on this trip, but the fact was it had passed us by, leaving us unscathed though more aware. Also, the driver promised to take us all the way home—if we survived the ride.

And truthfully, I was fascinated by the driver. He was an extremely dangerous individual—tough, experienced in life-and-death situations, and seething with obvious if suppressed violence. Clearly he had killed people—maybe a lot of people. Yet none of his violence and aggression were ever, even for an instant, directed toward his three passengers. I think we, as hippies, represented to him the real thing he’d been fighting for—not mom and apple pie and the military-industrial complex, but people who saw a better world in which individual freedom and lack of violence were the norm. He desperately wanted to identify with that world—that’s why he wore the peace symbol and had torn the sleeves and insignia off his fatigues. But he knew he’d seen too much of the wrong kind of life to ever be a hippie or even espouse the hippie philosophy. He was kind of like Billy Jack, seeing the idealistic truth in peaceful coexistence but too aware that violence is the real way of the world and too prone to violence himself to turn the other cheek.

In Johnson City, he stopped for gas at a redneck truck stop. I think he intentionally picked the worst one he could find. Glen and I weren’t too happy since the midnight chase across West Texas was sharp in our memories. Not that anyone would be able to catch up with this driver if he didn’t want them to—no sane person would drive like he did. But the problem was that he probably would let them catch up just to get into a ruckus. And now the rednecks who might cause us problems weren’t across the road or in pursuing vehicles—they were right there in the truck stop, and we were about to enter the lion’s den. Even the other freak was hesitant.

Maybe our driver sensed our reluctance. As he got out, he said jovially, “Come on in, guys. I’m buying.”

What else could we do? We were all hungry, thirsty, and needed the rest room, so we followed the driver through the door.

The tension inside was thick enough that movement was almost like swimming. Then one of the rednecks sitting on a stool at the counter turned and made a loud and somewhat threatening comment about it being time “to kick some dirty hippie ass.”

With an almost instantaneous predatory movement, our driver stepped uncomfortably close to the redneck—so close that the man couldn’t turn farther on his stool without bumping into him.

“You want to kick some ass?” the driver asked in a voice gone flat and totally devoid of emotion as he stared straight into the redneck’s eyes. There was no anger, no fear, no tension—only the question.

But it wasn’t his voice that I really noticed. Like I said, he was a big guy and pretty imposing, but where he’d shown us only joviality and camaraderie, he now literally radiated lethal menace. It was almost like standing in front of a heat lamp. I’d never felt such a thing before and never since, but I knew in that instant and without a shadow of a doubt that our friendly driver really had killed men who were trying to kill him. Maybe a lot of them. He’d looked them in the eyes and taken their lives, and he didn’t care if he did it again. He’d been trained well and steeped in the mysteries of dealing death, and all he needed to ply his trade was the flimsiest excuse from some idiot in Johnson City. I knew that if the guy on the stool and the other rednecks in the place tried to brace him, he’d walk away, but they wouldn’t.

Apparently, they realized it, too, for the one who’d spoken shut up and sullenly turned back to his beer, and the others followed suit. The tension in the room didn’t lighten, but suddenly it felt like we were in a protective bubble floating through it. The thing was, our driver was the nightmare of America’s war against the commies come home and shoved in its face. He was the soldier these men could never be and would always fear. They didn’t like him or the situation one damn bit, but there was nothing they could do because, unlike his passengers, he wasn’t a young and inexperienced guy. He was a maiming and killing guy.

We used the restroom, got our supplies, and the driver unhurriedly paid for them and the gas. As soon as we were back in the car, the driver’s demeanor shifted back to his jovial mode just as quickly as it had flared into the dangerous. He laughed as he pulled off, asking, “Did you see the look on that stupid asshole’s face?”

We laughed, too, because we had, though I think we were all a bit more wary of our driver now that we’d seen his scarier side. But that side never surfaced again, and when, just after daybreak, we arrived in Houston, he took Glen and me straight to the dorms. We told him that he and the other freak were welcome to spend the night and get some sleep, but he just pulled out his bottle of speed, popped a couple of more pills, and said, naw, he was anxious to get to Atlanta. Then the station wagon squealed out of the parking lot and disappeared up the street.

Glen and I turned, and there before us, lit by the morning light, was our dorm. It looked no different than it had when we’d left nine days earlier, but somehow it didn’t seem entirely real. Something had changed. We picked up our bags, went inside, and trudged up to our room.